The debate about the Labour party’s future has seldom been more parochial or inward-looking. Those who pass comment on Labour’s fate from the right and left of the party do so with an almost entirely British lens. In this insular universe, it is as if the world beyond the UK’s shores never existed. ‘Socialism in one country’ is back with a vengeance. Yet to recover politically and electorally, British Labour must learn from social democrats and progressive forces across Europe. There are three critical lessons from other countries that the centre-left ought to heed.

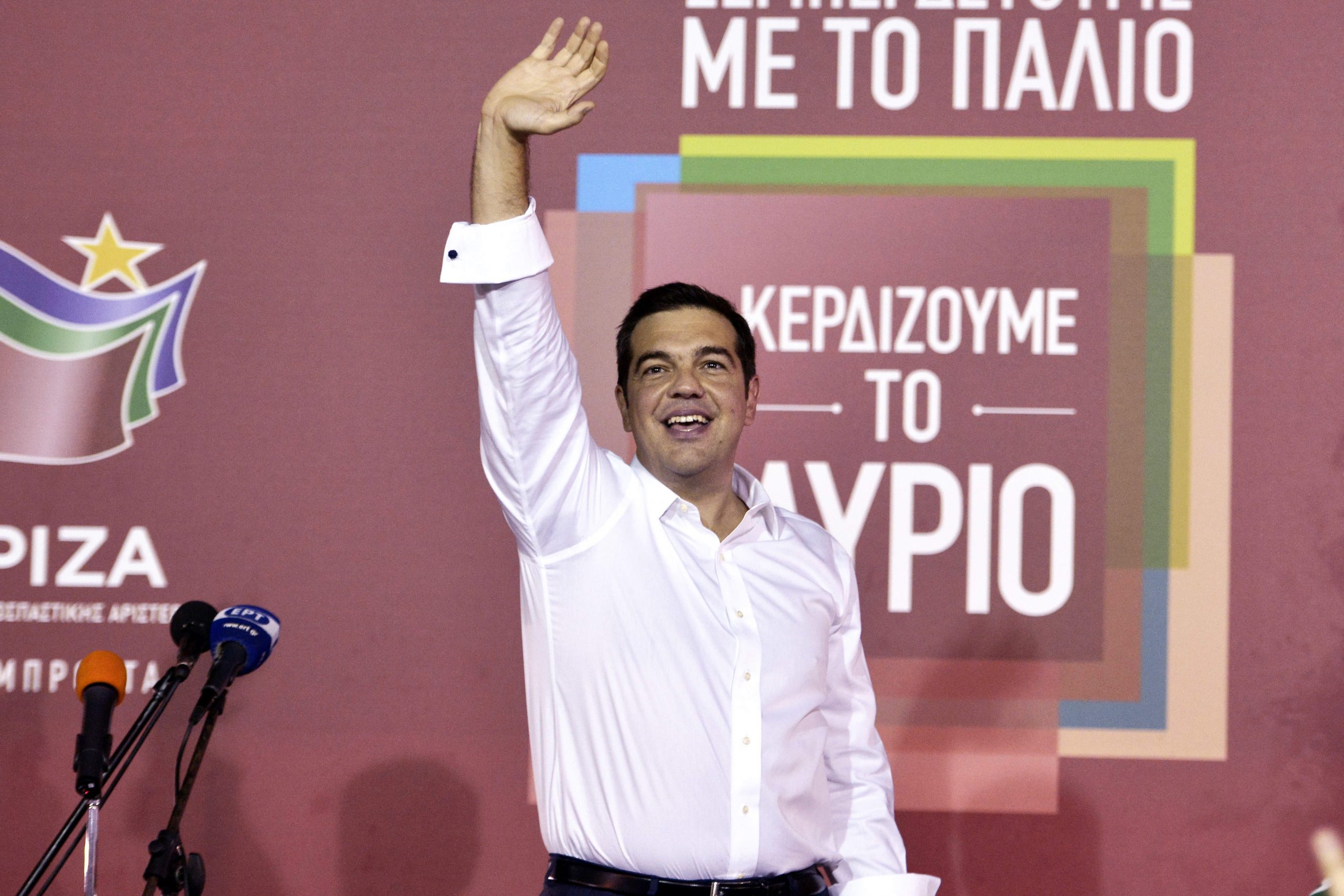

The first is that centre-left parties have to resist being squeezed between neo-liberalism and the new social movements. Yes, social democrats should rebuild their economic credibility and espouse a responsible governing agenda. But that should not mean rejecting all ties to social and environmental activism. The networked civil society is where most political energy and vitality currently resides in western democracies. The lesson of Podemos in Spain and Greece’s Syriza is that people want to be agents of change themselves, whether saving local high streets from unscrupulous developers or working to build their own affordable housing. Casting a ballot every four or five years no longer constitutes meaningful political engagement. Across Europe, social democrats have to form new alliances in pursuit of a better society reaching beyond traditional party structures.

A further object lesson is that opposition to austerity on its own is not enough to win power. Of course, premature cuts have weakened growth, jobs and living standards. In southern Europe, the masochistic pursuit of austerity threatens to unleash a social catastrophe. However, centre-left parties must show they would be competent managers of the economy articulating a coherent plan to deal with debt: not just net public sector debt over the economic cycle, but tackling unsustainable financial sector and household debt. Social democrats have to show how they would govern in a world where there is less money around for state spending after the great recession and the impending threat of secular stagnation. This demands a strategy for regulating financial markets that promotes the public good, tackles systemic risks and reforms banks that are ‘too big to fail’. An industrial modernisation plan would rebalance our economies away from their reliance on financial services towards knowledge-intensive sectors and manufacturing. In reforming the tax system, there ought to be a major clamp-down on cross-border tax evasion and fraud while restoring the progressivity of tax using redistribution to tackle new inequalities.

Finally, the left must not be distracted from confronting deeper underlying forces in politics. Centre-left parties are losing elections because voters don’t trust politicians to protect their way of life against the impersonal forces of global change. Europe has pitched dramatically to the right – not only towards Christian Democratic and Conservative parties, but new forces adept at exploiting voters’ fears about economic insecurity, immigration and hostility to the EU. In the UK, UKIP has now become the dominant challenger to Labour in northern England and the Midlands; last year, the Danish People’s party surged to power. In the heartlands of European social democracy, from the Nordic states to France and the Netherlands, right-wing populists are on the rise. In Austria this week, a hard right presidential candidate was in touching-distance of power.

The failure to counter the right isn’t just about poorly executed electoral strategies, weak leadership, or the price of incumbency in coalition governments: something more profound is going on. Regardless of national context, social democracy’s support base is being eaten away. The left is losing, not just on the conventional politics of economic competence, but increasingly on the vexed politics of national identity.

That said, the temptation to raise the drawbridge against immigration ought to be resisted. Flirting with a restrictive immigration policy is superficially tempting when the populist right is winning, but imposing arbitrary limits would be economically damaging as well as politically unprincipled. Instead, low wage and vulnerable workers across the EU ought to be better protected. Permitting the uncontrolled exploitation of low-cost labour in Eastern Europe has undermined the entire European project. More safeguards against agency working and zero-hours contracts are needed.

Rather than pretending that government on its own can do everything to shield citizens and communities from global market forces, the priority should also be to encourage intermediate institutions located between the central state and the free market that rebuild a sense of local attachment, recreate respect for traditional jobs and civic identities, and encourage a spirit of mutual obligation embodied in organisations like mutual’s and co-op’s. The left must end its ambivalence about English identity in the aftermath of devolution to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Labour must not be afraid ‘to speak for England’.

The centre-left must articulate its own vision of a cohesive society, backed by an understanding of sovereignty that accepts the nation-state is the central pillar of security and belonging. To navigate the hard road back to power, social democratic parties will have to acknowledge the communal attachments that give meaning to our lives in an era of unprecedented insecurity and upheaval. Only by securing the trust and allegiance of citizens within the nation-state can the centre-left win the argument for international engagement and co-operation: the cornerstone of a liberal world order.

Patrick Diamond is Co-Chair of Policy Network. The Progressive Governance Conference takes place in Stockholm 26-7 May 2016